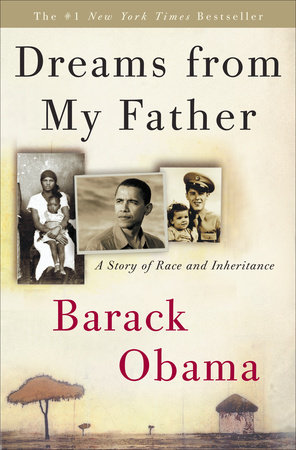

Oh my goodness, I am the worst book blogger in the world. In my defense, I have been DEEP into my feminist reading challenge, the results of which I’m excited to share with you, and living life, which can be kind of time-consuming. I’ve also been dreading reviewing Dreams from My Father because I struggled with how to appreciate it outside the scope of my curiosity about our President’s early life. I just have to admit that what I find most interesting about this memoir is largely attributable to the timing of its publication long before Obama could have dreamed of being President. At least, I have to assume: The book was first published in 1995, more than two decades before he ran for President, ten years before he was elected to the U.S. Senate, and two years before he held his first elected office as an Illinois State Senator. Dreams from My Father has none of the transparent self-interest of today’s political-memoir-cum-campaign-manifesto, and offers an expression of the life, values, and struggles of a U.S. President that’s unmarred by historical hindsight or political agenda.

The memoir is divided into three sections: Origins, about growing up within a white family in Hawaii and Indonesia; Chicago, covering Obama’s post-college years as a community organizer in the South Side; and Kenya, in which Obama meets his paternal relatives in Kenya for the first time and tries to understand a father he never knew. Origins has much in common with Americanah’s exploration of being black and African within different national contexts, and I can see why Ifemelu is such a fan. For me, though, Chicago was easily the most riveting section of the book. It recounts Obama’s early political activism as a determined but untested leader and delivers small but inspiring victories as well as cringe-inducing failures. Obama is honest about his frustrations during this time and makes it easy to appreciate the overwhelming challenges grassroots organizers face from existing political structures and their own discouraged allies. Within this context, “the audacity of hope” assumes its rougher connotations; it is truly audacious–arrogantly, foolishly bold–to persevere in the face of such entrenched and diversified opposition.

Kenya was a challenge for me. It presents a big topical shift away from Chicago and while Obama ultimately connects the themes and struggles of all three sections–his conflicted identity, the racial struggles of the U.S., and the legacies of his father and grandfathers–he also introduces many new characters and several rounds of lengthy exposition that can wear a reader out, which is pretty much what happened. I would love to return to this section with a little more brainpower one day, especially now that I have a some feminist theory under my belt and am more prepared to recognize how patriarchal patterns link racial and national struggles with gendered ones. For Obama, this realization, though not expressed in overtly feminist terms, is a key to understanding his complicated inheritance and unlocking his future.

Overall recommendation: Worth reading if only to see what time and politics have done with Obama’s story, and to trace his values and legacy back to his origins. A convincingly honest portrait of a young leader and young man.

Overall rating: 365 out of 538 electoral votes

Books read: 7 out of 50. Don’t even want to reveal how far that puts me behind schedule, but I’m on it!