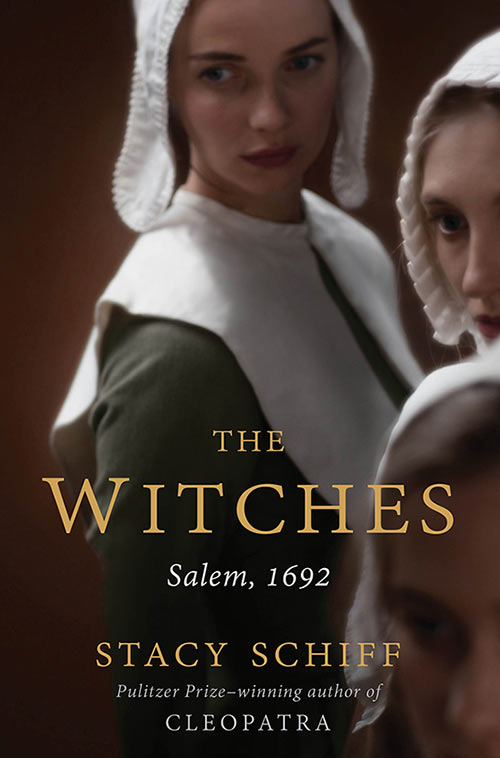

Well, folks, it took me twice as long as I expected but I did it; I finished this 500-page history of the Salem witch trials–a topic it turns out I knew pretty much nothing about. Apparently multiple viewings of Hocus Pocus does not a historian make, so I blame myself for taking so long and for ultimately failing to appreciate what’s probably a superb history.

The Good: The Witches’ great feat is constructing a coherent narrative out of incomplete, biased, and purposefully obscured records. As Schiff explains, even when it could be heard over the din of Salem’s raucous meetinghouse, trial testimony was regularly garbled, often plain omitted if the record-keeper deemed it unimportant or an obvious lie, as most denials were. Some of the region’s most meticulous record-keepers decided to keep silent until after the events of 1692 had subsided, and the legal and moral authorities entrusted with interpreting the Salem witch trials provided the most equivocating and ambiguous written guidance. With meager historical help, Schiff pulls together the threads of Salem’s story and provides an intelligible timeline of events and roster of participants.

The Bad: Perhaps unfairly, The Witches also suffers for its narrative integrity. The book proceeds chronologically, with Schiff reserving all but the most glancing analysis for the book’s penultimate chapter. The early chapters verge on tedious; once the initial suspects are named, the accusations pile up in a laundry list of complaints. The trials themselves follow the same frustrating but tired patterns. On the one hand, Schiff’s thoroughness is admirable for its historical integrity and research. On the other, it dilutes the more memorable and meaningful storylines with a disorienting array of names and repetitive details. The reader is awash in Marthas, Marys, Elizabeths, and Sarahs. Even the demonic imagery that so excites the people of Salem grows dull–witches so regularly balance on meetinghouse rafters, stab their victims with phantom pins, and suckle all manner of cats, birds, monkeys that it gets old. The book’s insights and themes, though fascinating, are more suggested than explored, and I think it would benefit both the storytelling and the reader’s historical understanding if The Witches were more thematically organized.

To borrow a word from Salem’s tergiversating magistrates*: nevertheless. I learned a lot. I learned that most of my pop culture-derived ideas about Puritan life and witchcraft were morbidly romantic and wrong. I learned a few other things, like:

- There were two Salems: Salem Town and Salem Village, and they did not get along. Salem Village wanted independence from the Town, which depended upon the villagers for agricultural goods but taxed them and required them to regularly travel the long and dangerous distance into town for military duty and church services. Witchcraft accusations broke out in the village and spread to the town. Salem Village did eventually get its independence from Salem Town and is now Danvers, MA, which has a reputation for being close-lipped about the past. Salem Town kept the Salem name and capitalizes on its history.

- It all started with YOUTHS. The first two victims were younger than the rest, no more than 12, and may have been suffering from the symptoms of conversion syndrome, experiencing the stress of living under the strict scrutiny of their minister father/uncle, Samuel Parris, as painful stabbing and pricking sensations. Their 17th century doctor, unable to provide a conventional diagnosis, deemed them bewitched. Soon, village girls in their teens and twenties claimed similar symptoms, probably motivated by a desire for attention and special treatment that would get them out of chores, which they absolutely got. The witch trials proved so distracting that they severely interrupted agricultural and economic activities in the town and even prevented the constable from collecting enough firewood to get his family through the coming winter–so busy he was arresting witches. The young women were the stars of the trials and were often called upon as visionaries to determine the source of mysterious afflictions, something this former teenage girl– who needed X-ray evidence to convince parents and gym teachers of broken bones–will never understand. What happened to the credibility of teenage girls between the 17th and 21st centuries that could explain such a profound reversal??

- It happened and was over very quickly. The first witchcraft victims were afflicted in January and the accusations began in February, with trials taking place throughout the spring and summer. The convicted were executed June-September and by October the trying court was dissolved by the Massachusetts governor. From October to February of 1693, the evidence that had led to convictions was discredited and dismantled and the remaining suspects were released, though they would never escape the stigma of being accused.

- People were assholes. Few were innocent during the events of the Salem witch trials, but mass hysteria doesn’t really explain the jerk behavior of the neighbors and town authorities who took advantage of the situation to steal from the accused. As soon as an accused witch was carted off to prison to await trial, these prominent and powerful folks would seize his or her now-vulnerable property and distribute it among their allies, making the odd exception for an exorbitant bribe–all before a conviction. Families were financially ruined while loved ones languished in jail and children who were unjustly orphaned could not get restitution even after their parents were posthumously pardoned. Though regret set in quickly, reparations were rarely and belatedly granted.

- People really did believe in witchcraft. And it wasn’t just the fearful, fear-mongering masses. Given the risk deniers faced of being accused, there was little choice but to publicly believe in witchcraft, of course, but even outspoken skeptics readily acknowledged their belief–it wasn’t the existence of witchcraft they questioned, but the ability of men to identify its practitioners. The suckling birds and spectral visitors of witchcraft were hardly far-fetched to a population conversant in the satanic snakes and resurrections of the Bible. Indeed, to deny witchcraft was to contradict the Bible (which was, unfortunately, a little unclear about what witches were) and borderline heretical. Puritan religious guilt was moreover ripe for exploitation; it took little logical maneuvering and psychological torment to convince some pious accused–who found themselves spiritually delinquent in the best of times–that they were witches.

Overall recommendation: Best for history buffs, perhaps? I wanted to love this book, but I only liked it. I did not find it nearly as vivid or thrilling as the jacket copy promised but I did learn a lot.

Overall rating: 6 out of 10 flying poles

Books read: 4 out of 50. According to Goodreads, this puts me 1 book behind schedule. To compensate, next week’s reading assignment is a Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie double feature: Americanah and We Should All Be Feminists.

*Please forgive me for this phrase. I just learned this word and could not resist.